Wednesday, 6/1

The transition from coastal Highlands to urban Edinburgh was not entirely smooth. We spent roughly an hour circling Waverley Station looking for the Europcar rental dropoff, getting the distinct feeling, like centuries of other foreign invaders, that all these stone walls were completely impenetrable. After getting instructions from an annoyed man at the other end of a crackly speakerphone at the bus pickup to "take four straight left turns and keep going down" that were, incredibly, correct, I told the Europcar representative as my wife handed him the keys that I felt like we were in some heretofore undiscovered ring of purgatory. "That bad, eh?" he said, walking away. We then walked with our luggage the roughly half-mile to our AirBNB in the Grassmarket, a trek that seemed all uphill. Once we got to our apartment I took a short nap, and woke up with a bit more perspective. I always have a hard time adjusting when arriving in a city I've never been to; I think this might be at least in part because I want to feel at home immediately, as if there is some urbanite code I'm proxy to. But cities just don't welcome strangers that way. They might feign a welcome at tourist destinations like the Royal Mile and the Grassmarket where we were staying, but even a little perception makes it abundantly clear that this city, as with any city, existed well before you, and is functioning just fine without you, thanks. But the early glimpses are the ones that stay with a visitor - angles, openings, perceived familiarities, all of which greeted us when we left the apartment to venture forth into the Edinburgh evening.

The view from the door to our AirBNB apartment building

At the notable corner

We had dinner at a steak and mussel place, which allowed us to inject ourselves into one of the most aesthetically interesting urban street corners in the world. Then, determined not to waste a minute of our one day and two nights together in Edinburgh, we found a literary pub tour. Led by two actors, one of whom plays a bohemian drunk and the other a literary scholar, the tour started at the Beehive Inn at the Greenmarket public square. No photos were allowed on the trip, which I was fine with; it was an active and lively tour, and we definitely would have missed something if we'd taken time to snap photos. The two characters talked about Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, and others, all while negotiating with locals hanging out in the closes outside the pubs where we were hanging out, including a homeless man walking his bike and howling in pain at some unseen horror (during the Stevenson/Jekyll and Hyde segment, by the way). After the official part of the pub tour concluded on Rose Street in New Town, my wife and I hung out a bit with the two actors, free-associating about frankfurters, papaya, Stevenson's "Apology for Idlers," and curriculum development (my wife's ostensible reason for being in Edinburgh). I left thinking I had a possible essay that we collectively dubbed "Here We Go Again." This paragraph will probably have to suffice.

Thursday, 6/2

Edinburgh Castle was the first we visited that felt alive—not rebuilt or left in ruins, but crawling with activity. Government officials marched to their duties flanked by high-stepping military, cannons loudly saluted the noontime hour, a band marched playing the theme from Star Wars (brazenly playing Darth Vader’s entry music as a series of high-office officials walking into their building). If Stirling Castle felt like a once-teeming metropolis, Edinburgh Castle felt like the metropolis’s crown jewel. And it didn’t hurt that it actually houses the crown jewels.

Next to Edinburgh Castle is the Camera Obscura, which houses more than a century of optical illusions, musical contraptions, magic even. We ascended too quickly for me to know this for sure, but I got the feeling going from the first through the sixth floor and onto its roof that each floor took us further into the past, to the root impulse of the original camera obscura—taking the real and making it unreal. This alone allowed me to contextualize the unreality of the spinning tunnel thing on the first floor that had me clutching the rails dizzily despite the room not moving at all, and the sense, in the dark with a roomful of other tourists, that I was watching the street below with a child’s awe, not as a piece of contemporary infrastructure but as an ancient, ageless reflection that our barker could manipulate simply by moving the mirrors.

We spent a half hour observing Scottish Parliament at the startlingly modern building (so modern, in fact, that I found it too ordinary to photograph). During our time there they were arguing about benefits and entitlements for the elderly and disadvantaged - similar issues our American congress argues, though we're only allowed to observe it on C-SPAN. I couldn't help thinking how I've now seen in person more of the inner workings of Scottish government than my own.

Perhaps the only aspect of the Edinburgh landscape that can overshadow Edinburgh Castle is Holyrood Park, a gargantuan lump of land on the other end of the town square that we could see from every vantage point in town. From a distance it looks like a single mountain was removed from the highland coast and dropped onto the city near parliament. At its peak is the mystical Arthur's Seat, which may be but was probably not the site of King Arthur's Camelot. As we approached the mount, we looked at the map of possible ascents, but decided to to follow the trails that generally went up. Either we seriously underestimated the time and distance to the top, or we took the longest way possible. Either way, it was worth every step. We traversed stone steppes (that spelling just feels right here) and vein-like paths up and around the goliath, looking up and down a green and blue and dots of yellow gorse all around us. We saw the ruins of St. Anthony's Chapel and followed blackbirds around the bends, where they caught wind and floated in the breeze coming from the water we didn't know until then surrounded Edinburgh on most sides. And when we reached the top together, I looked at my wife and felt a fire burning inside me that was so intense I thought my chest would combust. And I looked at the other people gathered around Arthur's Seat - parents with small babies, teenage and twenty-something friends, speakers of languages I didn't understand - and for these moments I was completely sublimated in a beloved community of fellow wanderers, souls joined together at this summit for just these few specks of eternity.

Steppes

The veins

St. Anthony's Chapel

Arthur's Seat

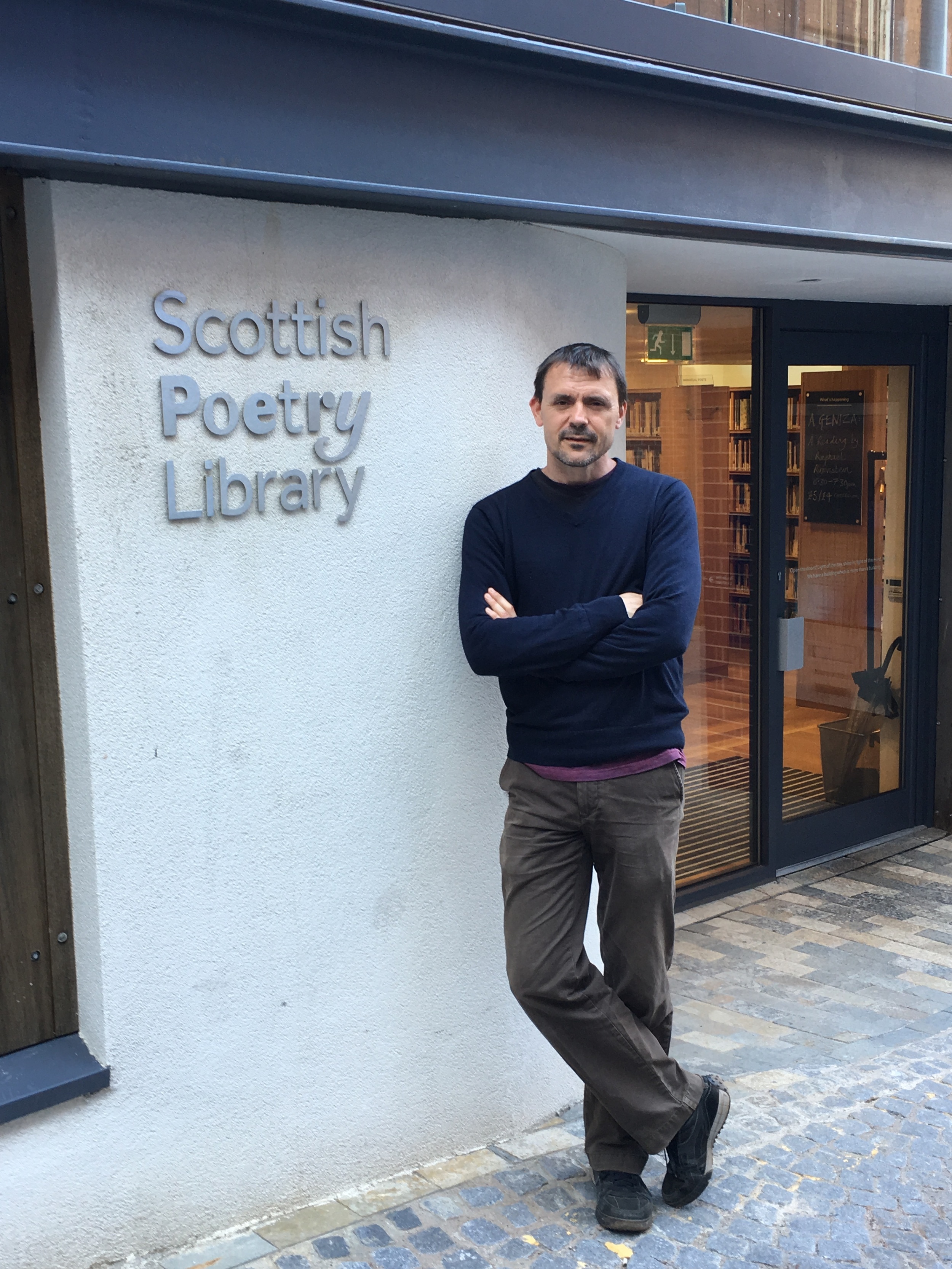

I must qualify, before saying another word to recount my two days in Edinburgh, that it rained not a drop during any hour of our stay. I felt a little guilty when I read Stevenson's words from the first couple of paragraphs of his essay "Edinburgh" in the Scottish Poetry Library on our way back from Holyrood Park: "The ancient and famous metropolis of the North sits overlooking a windy estuary from the slope and summit of three hills. No situation could be more commanding for the head city of a kingdom; none better chosen for noble prospects...But Edinburgh pays cruelly for her high seat in one of the vilest climates under heaven. She is liable to be beat upon by all the winds that blow, to be drenched with rain, to be buried in cold sea fogs out of the east, and powdered with the snow as it comes flying southward from the Highland hills." From this and from all I understand about Edinburgh - hell, about Scotland - I feel the need to equivocate that our stay should be taken with a grain of salt, or perhaps as a grain of sand, miscolored but not prominent enough to be noticeable in the vastness of the lovely town's historical landscape.

Friday, 6/3

I left Edinburgh first thing in the morning. My wife walked me to the commuter bus just after sunup. Riding through New Town, I wondered if I would ever get to know this city any better. While on the moving walkway on my way to my plane at the airport, I noticed a quotation from historian Murdo Macdonald:

This got me to thinking about my initial comeuppance on entering the city, and the deepening sadness I felt as I got to know it better, knowing how little time I had here in Edinburgh, in the highlands, on this stony archipelago. Cities—like the land and sky, like people—are never completely knowable. Every person to interact with them, whether for a day or a week or a lifetime, brings upon them one’s own preconceptions, expectations, and mythologies. In this way, they are maps for finding ourselves.