“Notes Toward a Working Definition of Mopecore,” published in the anthology Beyond the Rhetoric of Pain [Routledge]

From editor Berenike Jung’s introduction:

"John Proctor's contribution begins with a touching story narrating the anguish of his small daughter about the death of a fictional cat...Her grief taps into a deeper truth, which Proctor connects to both a historical and a very contemporary pain...Proctor consults an array of late-twentieth century thinkers and theorists as well as representations in literature, film, and television, to demonstrate the proximity of laughter and tears, but he also opens up an intensely personal and deeply touching witnessing of this moment."

"May 17, 2017," Past Ten, 5/17/17

"I believe that something happens to the mind and the heart when one comes to a full understanding that one’s life doesn’t have to mean anything, that getting through it without making much noise is what is expected of us. Bending one’s own will to the rhythms of the world is natural. Only something unnatural has happened to our world in the last century, the rhythms of industry and consumption and simulacra replacing accumulated wisdom, empathy, the real. Sitting here in this manicured landscape modeled on a musical fiction about the worst mass genocide of the past century, the span of not just ten but a hundred years spread out before me, and all I could think was, You are complicit."

"The Beginning and the End," included the anthology Minificción y nanofilología: Latitudes de la hiperbrevedad, an anthology of microfiction published by Iberoamericana-Vervuert (Madrid/Frankfurt)

"Sometime in 2001, I started but never finished a piece called 'Completion (A Work in Progress).' Its de facto last line is, 'So when I leave...it’s not because I’m lazy, or stupid, or...it’s because I refuse to...' I struggle, as I live and read, read and write, write and compile, with the recurring conviction that this will never be done. Twentieth-Century philosopher Richard Rorty said that the pragmatist’s awareness of the world was not a progression but 'contingent results of encounters with various books which happened to fall into one’s hands.' Summary listing can give a person a sense of the bigness of life—historical, biological, psychological, philosophical. But foremost among its risks is the temptation to presume any authority over the chasm simply because one can hear one’s own echo when screaming into it. Or even to assume authorship of the echo."

"The Eternal Return of the Grievous Angel," New Madrid Journal of Contemporary Literature, Summer 2016

"I desperately wanted not to remember him as the beaten man fading into the walls of his rented flat, the hophead electrician some people of the town would undoubtedly use as an example of what can happen to anyone daring to step outside the bounds of conventional morality. No, I wanted desperately to remember the Blakean man-beast, pure energy bound by no reason, and the Nietzschean will to power, bound by no law, who could through the force of his own nature evade or destroy anything in his path, the world if necessary, and throw it all at my feet. I wanted him to be the myth I’d built around him."

...

"I saw across the table from me a man whose brother had just died, who couldn’t even allow himself to grieve—a man doomed to relive his mistakes until his own death, whose funeral the child to whom he’d given over his youth and his purpose would almost certainly not attend. I saw in him the immutable truth that we are all grievous angels, returning eternally to the scene of our first demise."

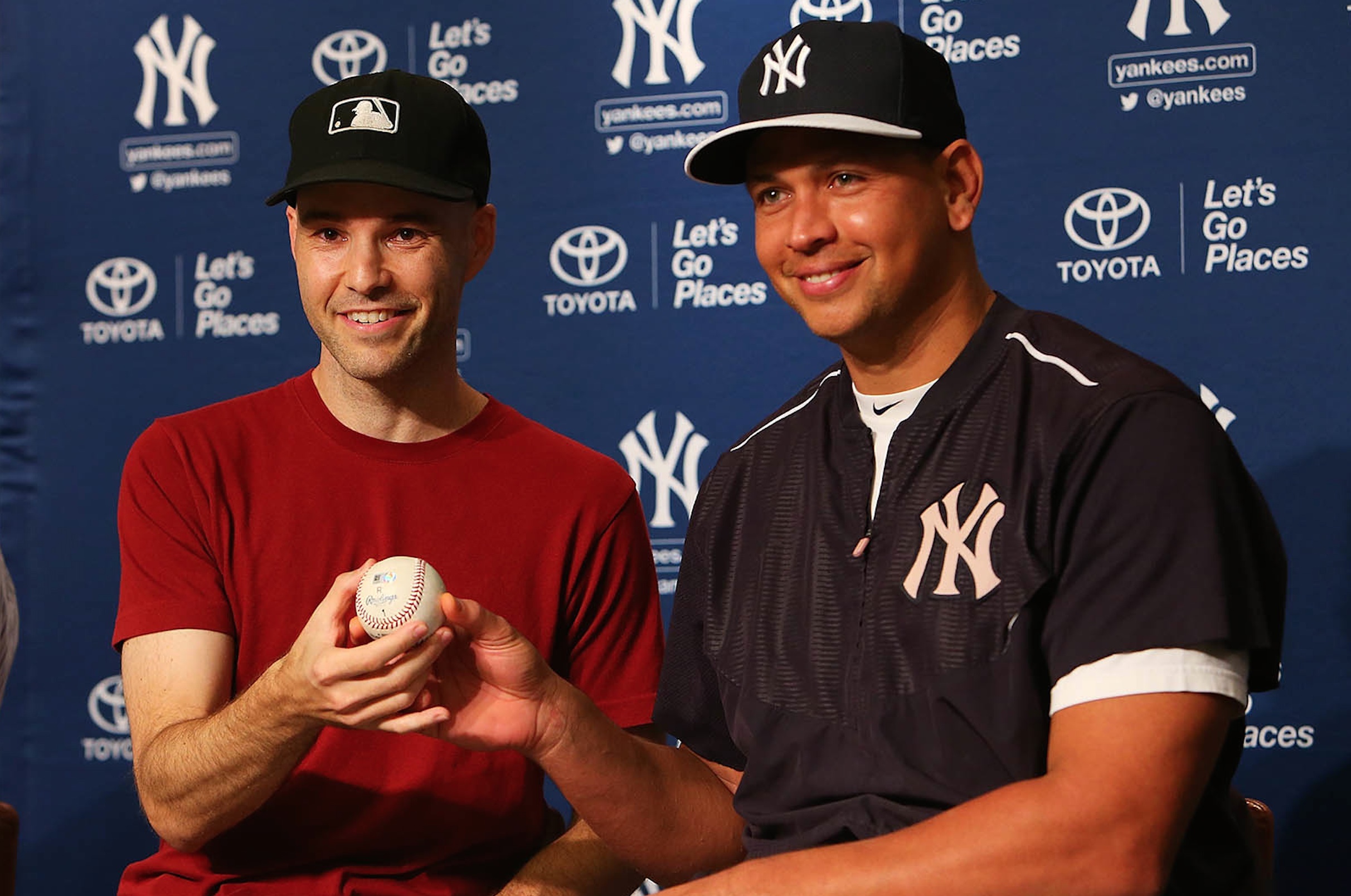

"My Summer with Zack Hample, the A-Rod of Ballhawking," The Weeklings 9/30/15

"Perhaps the most elucidating thing Hample told me in our first conversation was this: 'You should know that anyone who hangs out in the stands at baseball games with any regularity is not to be trusted.' To which he later added, 'Except me.'"

"Meditating Underwater," Atlas and Alice Literary Magazine 8/24/15

"At 6:00 p.m. I don’t call my sister. I don’t call my brother. I won’t hear about my mother’s condition until hours later, presumably after my stepfather has gone through his long list of whoever he has to call before me. People are gathering for dinner upstairs, and I’m sitting alone on the bed. My stepfather and sister will exchange words as soon as my mother emerges from her anesthesia. I won’t know what they are, but I’ll know from my stepfather that her first words will be, 'Stop fighting.' At this moment, I won’t want to fight, or to eat dinner. I’ll just want my mother, whose first task will be learning how to walk again."

"Return of the Repressed," The Weeklings 4/6/15

"As a longtime Royals fan, my heart has been destroyed regularly by a game that, as A. Bartlett Giamatti said after his beloved Red Sox had once again been eliminated from playoff contention in late October while the hated Yankees played on, “was designed to break your heart.” But, on this night and the month of October that followed, I discovered how flippantly the game can restore it."

"The Question of Influence," The Normal School, Volume Seven, Issue Two

"Through my first 17 years I had three names; two mothers, one of whom died when I was young; and a multitude of fathers. I left home then, and started anew. The words I read became my family, my tradition, my primary influence. My family now is a set of literary tropes, no more real to me than John Proctor in The Crucible or the Talking Asshole in Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. It’s no coincidence that my name shares space with the American canon. They both made me."

Buy the issue online here, or pick it up at your favorite (hopefully independent) bookstore!

"The Love Song of Kumquat J. Farthing," The Austin Review, Issue 2, June 2014

"Some words just sound dirty. So when my brother Justin showed me an email he'd received from Mr. Kumquat J. Farthing, I naturally assumed he'd been using my business computer to look at porn."

"My life could be boiled down to a handful of jokes I've told and retold, mostly from childhood. I enjoy this about myself—jokes are like tall tales, where we know how they end but we act like we don't on the off-chance that we can fool ourselves into being surprised and delighted by the time we get to the ending, which always makes us smile. Telling a joke well is something even dictators and killers respect, because the power of a well-told joke is freely given by the audience. My jokes are my stories, the parts of my life I've sharpened to a fine point, the punchline. People don't mind being misled, if there's a good turn at the end of the plank."

"For about four weeks now, our 2000 Honda Civic has been making a funny noise when we start it in the morning. My wife was the first to notice-kind of a whirring, whistling sound when I give the car gas, which runs its course after I pump the pedal two or three times. We'll ask when we take it in for a checkup next week, but I already recognize the sound. At first it seemed just vaguely familiar, but this morning the memory came back to me while I was pumping the gas, in one mad, mixed-up torrent. I heard this sound every morning during the summer of 1996 while hiding in the bushes at 6:00 a.m., night after long sleepless night, from another Honda. It's the sound of death."

"I moved to Brooklyn after reading a book about Brooklyn. I wanted to have a family in Brooklyn, to be a Brooklyn family, to be Eugene in Brighton Beach Memoirs, or Woody Allen in Annie Hall. I wanted to be educated, cultured, a Dodgers fan, even Jewish."

"The crab I’m thinking about, the immortal, is the stuff of books, of dreams, of the imagination. It is this crab for whom death matters so much that it would give up its life so that others may live after it. This crab, like a grain of sand on the beach that looks out on the ocean’s endless horizon, is meaningless in and of itself as it is tossed along that merciless, endless ocean. But trap it, isolate it, take it from its habitat, and it becomes something quantifiable, the dream in tangible form. Like a good book, or a work of art, or a song, this captured crab is the crossroads between dream and reality, and the only way we can get to it is to throw the steel traps of our minds out randomly into the boundless ocean of human discourse."

"This is all to say that the darkness of my 5:00am walk to the subway feels a lot like a movie set in Brooklyn. While the walk to the N train is a couple blocks shorter, I always walk the extra two blocks to the F. Eschewing 4th Avenue with its monstrous, crouching, half-built condos and Fort Hamilton Drive’s view of the industrial core of Brooklyn and wind that can drive a person backward, I choose the narrower Brownstone-lined thoroughfares that never threaten my own fragile sense of my neighborhood’s smallness in the guts of Gargantua."

"When I was in grade school, William S. Burroughs visited my house. At least I think so. Strange old men with secrets were fairly commonplace in Lawrence, Kansas...Old Man Burroughs didn’t say a word directly to me until he’d laid out his case to my parents. He then looked directly into me. 'You should know,' he said, 'that I’m quite proficient with a handgun.'"

"Converting the Lovebugs," Perspectives Volume XXVIII 2005/2006

I wrote this piece in 2005 from my journals while doing some minor post-Katrina relief work. It was published in Perspectives, the faculty literary journal of the New York City College of Technology, which means almost no one read it when it was originally published. The piece holds a special place in my heart and in my oeuvre. I thought of it as a piece of literary reportage at the time, but I was, in retrospect, writing one of my first personal essays.

A LITTLE CAVEAT, THOUGH: Snopes.com has verified the falsity of the claim that lovebugs are a genetic experiment to combat the mosquito population gone awry. They in fact are native to Central America, and probably were brought into the US sometime around 1920 on the cargo ships that ported in New Orleans, Florida, and other ports on the Gulf of Mexico. Just so you know.