“Notes Toward a Working Definition of Mopecore,” published in the anthology Beyond the Rhetoric of Pain [Routledge]

From editor Berenike Jung’s introduction:

"John Proctor's contribution begins with a touching story narrating the anguish of his small daughter about the death of a fictional cat...Her grief taps into a deeper truth, which Proctor connects to both a historical and a very contemporary pain...Proctor consults an array of late-twentieth century thinkers and theorists as well as representations in literature, film, and television, to demonstrate the proximity of laughter and tears, but he also opens up an intensely personal and deeply touching witnessing of this moment."

“It Be Like That but Sometimes It’s Not, and The Present Life of Alexandria and Nykeira,” Essay Daily, December 4, 2018

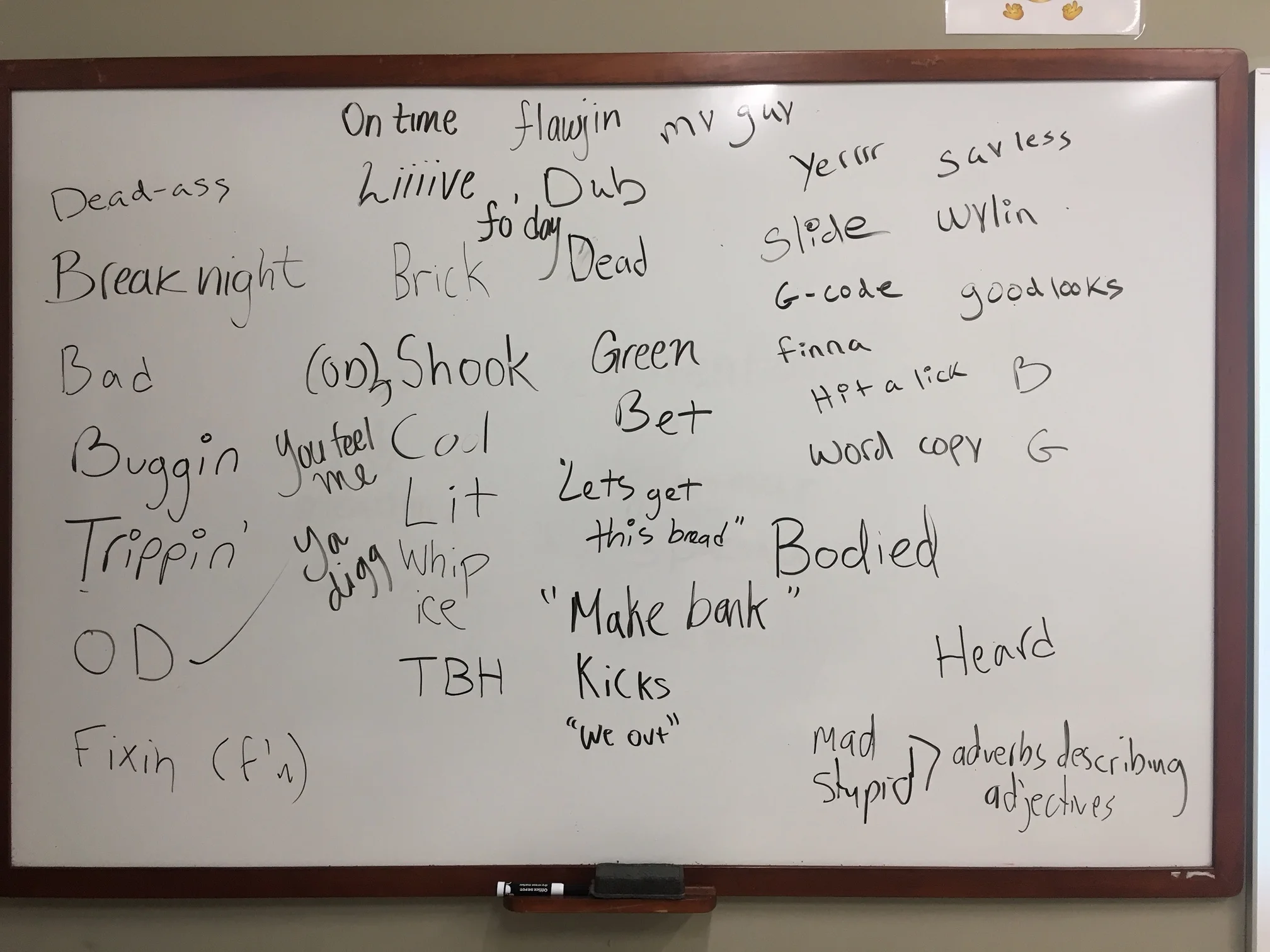

“As a white person in a position of given authority, I can’t understand the ‘rules’ of Black English that June Jordan and her class identified, because I haven’t had a background or experience that informs them. I am a middle aged white guy, informed by decades of experience as such, and I can’t use an expression like ‘It be like that sometimes’ without the person I’m speaking to thinking I’m joking, even if I don’t intend it…We are unfortunately still living in an era in which cops are allowed to shoot unarmed black men with impunity. We are, though, hopefully now living in an era in which educators think about the ways their teaching is informed by the same systemic racism. It is only a matter of degrees between comfort in appropriating linguistic usage and excusing a person in a position of authority for performing acts of violence on those people whose language we steal.”

"Nothing Out of Something: Diagramming Sentences of Oppression," Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies 5.1, Fall 2018

"Language is also the primary paradigm governing the structural understanding of ourselves, and as such is perhaps the most powerful tool not just of academic disciplines, historical narratives, and generational tradition, but also of repressive governments, rapacious industrialists and capitalists, and dusty schoolmarms and mansplainers. To Control the Message is to dictate how to use our common language: to put it in a box, to diagram its meaning as if any word or sentence or thought had only one meaning, as if any person or institution had the right to impose that meaning on the rest of our shared world."

"How Can I Explain Personal Pain?": On Tatiana Ryckman's I Don't Think About You (Until I Do) Essay Daily, January 22, 2018

"The one quirk of the essay as a form with which I struggle most is its presumed narcissism. The form almost requires its writers to talk to themselves for an audience. This becomes especially fraught when relating personal pain...The poet Ralph Angel once told a woman he was advising at the graduate school Ryckman and I attended to “get naked on the page”; she responded by dipping her breasts in paint, pressing them against paper, and submitting them with a statement of intention. One can’t be sure, but I don’t think that was what he was requesting. To get naked on the page—to confront our pain and confusion and mold them into language—requires a blatant disregard of our impulse toward emotional self-preservation. If we press our most private parts onto the page, it’s not paint that records and preserves us. It’s blood."

"Teachin' BAE: A Reclamation of Research and Critical Thought," Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies 3.1, Fall 2016

I wrote this critical piece as part of the Best American Essays Spotlight series at Assay. The series also includes a fascinating interview with luminous BAE editor Robert Atwan, Jenny Spinner's "Best American Essays Series as (Partial) Essay History," and Lynn Z. Bloom's "The Great American Potluck Party." Great company to keep, methinks.

"In the last sentence of his postscript to 'Independent Redundancy,' the mammoth centerpiece essay of his new collection, Patrick Madden quotes Gide: 'Everything has been said before, but since nobody listens we have to keep going back and beginning all over again.' This might be just a bit too morose to serve as an unqualified summation of Madden’s essayistic perspective, but it’s pretty close. To read a Patrick Madden essay is to interface with the mind of an engaged, self-conscious thinker. Actually, that’s not quite right: It is to interface with Madden’s curation of the minds of many thinkers within the expanse of his own."

Essay Advent: Best American Essays 2004, Essay Daily, December 2015

In December 2015, Essay Daily ran a fun "Essay Advent Calendar," wherein each day a different writer wrote about a different volume of The Best American Essays. On December 4, I did 2004.

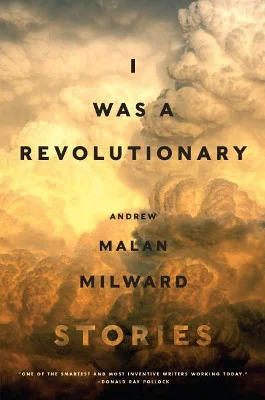

One of my summer reads this year was on the suggestion of Steven Church, who asked me if I'd like to review Andrew Malan Milward's short story collection I Was a Revolutionary for The Normal School. It's a really great read, an we had some great conversation about it, now up on TNS's website.

"I’ve always wanted, though I didn’t always know I wanted, to write more like a song than a story. I’m tempted to say Steven Church does this, but on second thought this explanation might be looking at these essays from the wrong end of the earpiece: I think he writes like I listen to a song."

"The chapbook contains five essays, one about her alcoholic lover, another about a magnifying glass by which she detects elements of her world, another about a vaguely sexual prank phone caller, another about her sleeplessness, another about the wind. Each of them, whatever its ostensible subject, is as much an assemblage as a narrative, turning over each element in her palm and mulling it over with the care of a collector and the passion of a paramour. When I open it and take in Steiner’s masterful prose, and even when I simply open the book and hold it in my hands, I think not of a reading but of a conversation, of a voice offering no answers and telling no lies, but rather setting up the riddles so that every response, so long as it is honest, is the punchline."

Last December, I edited for Hunger Mountain a celebration of of Baldwin's life and work on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death with Jennifer Bowen Hicks, a born-and-bred Baldwinite both in terms of her commitment to her craft and her intense empathy and commitment to social service (besides writing, she runs a writing program for prisoners in the state of Minnesota). If editing the project taught me anything, it was the deep and abiding love of Baldwin many writers share with me. The project includes contributions by Kim Dana Kupperman, Sion Dayson, Carole K. Harris, Robert Vivian, Marita Golden, Baron Wormser, and Liz Blood. You can find all of them here. [UPDATE: Kim Dana Kupperman's piece was selected as a notable essay in The Best American Essays 2013 !]

In 2009, in order to sublimate myself to the essay as a form, I began reading each volume of The Best American Essays , one volume a month in reverse chronological order. This lasted for about a year, or until I got to 2000; I now satisfy myself with just a handful of essays each month from the remaining volumes. While I was reading a volume a month, I began writing "Sideways Reviews" for Hunger Mountain in which found something novel in an essay or series of essays and responded to it in whatever ways I saw fit. My wonderful editors Cynthia Newberry Martin and Claire Guyton then did their best to get the reviews to make some sort of sense. These are those reviews, nine in all, with a convenient Table of Contents from Hunger Mountain's website.

"If the nonfiction writer’s subject is the world, and his or her place in it, the first responsibility of the writer is to reduce the world into workable units. Much like a reader must read something numerous times to piece out the analog parts and then find the digital circuit at work, the nonfiction writer must find the story-units in the world and then fit them into a working digital circuit of the writing. In telling the myriad stories the world and the self contain, one of the writer’s first steps is shaping and condensing systematic and narrative units. For our purposes here I’ll coin the term “digital nonfiction” for this process – if an essay or a memoir or a news story (and, universally, the world) can be thought of as a digital circuit, and if all the millions and millions of stories are the analog parts, then the creativity of the nonfiction writer is primarily on how the writer sorts – or lists – those analog stories."

I wrote each of these pieces in successive months of the fall of 2010, when I was first exploring the personal essay as a form, something one simply can't do with any sense of history or purpose without ingesting the work of Montaigne, the "Fountainhead" (to quote Phillip Lopate) of the form. As with my previous Numero Cinq work, much of this made it into my later treatise on digital nonfiction.

These two pieces were my first explorations into the nature of creative nonfiction and the personal essay. My editor (and first-semester MFA advisor) Douglas Glover displayed remarkable indulgence in publishing them.